A water droplet that freezes from the outside in, shows an exciting series of rapid physical changes before it violently explodes.

This is shown by University of Twente researchers in their paper in Physical Review Letters of February 24, marked as ‘editor’s choice’.

A perfectly spherical droplet of water that freezes from the outside in, forms a shell first. This has the diameter of the droplet. As the shell thickens inward, the remaining water ‘gets a problem’: it wants to expand, but is confined by the shell. After some time, this causes the droplet to explode. But what happens in between?

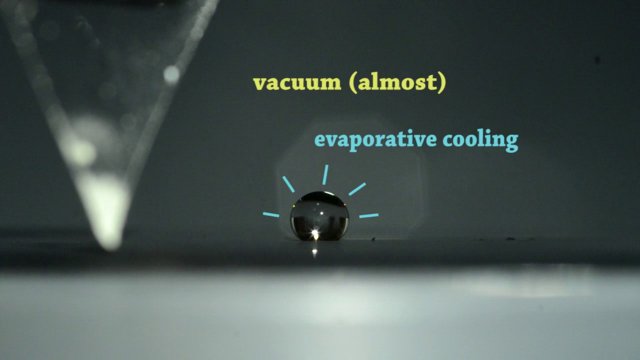

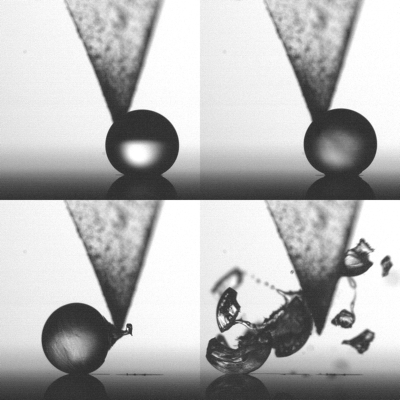

Droplet of supercooled water freezing from the outside in and exploding in the end. By touching it with the triangular tip, crystal formation starts

Shell formation

For creating spherical droplets, the UT scientists have placed them on a hydrophobic surface, in a vacuum chamber. The temperature is lowered by evaporative cooling so that the droplet is ‘supercooled’: the temperature is well below zero but the droplet doesn’t freeze yet. The first ice crystal is formed by touching the droplet with a silver iodide tip. A shell of ice forms rapidly, thickening from the outside in. The high speed video images show that cracks are formed in the shell, that a peak is formed and vapour cavities are formed underneath the surface. After releasing some ice flakes, the whole droplet explodes in the end. The ice parts have velocities of about 1,5 m/sec.

Clouds

The mathematical model Sander Wildeman and his colleagues developed for explaining this series of events, show that there is a minimum droplet size: below a diameter of 50 micron, no explosion will take place. Meteorologists already know the phenomenon of droplet explosions in the cold tops of clouds. They play a role in the onset of precipitation and can lead to the rapid transformation of a cloud with fluid droplets to a cloud of ice droplets.

‘Dutch tears’

The experiments have some resemblance to a well-known way to produce hard glass, already known to Dutch glass-blowers in 17th century. Droplets of molten glass, put into cold water, also solidify from the outside in, forming a shell of glass around the melt. They are also known as ‘Dutch tears’. The difference with water is that glass shrinks when it becomes solid. This makes the glass sphere very strong.

The research has been done in the Physics of Fluids group of Prof. Detlef Lohse. This group is part of UT’s MESA+ Institute for Nanotechnology.

The paper ‘Fast Dynamics of Water Droplets Freezing from the Outside In’, by Sander Wildeman, Sebastian Sterl, Chao Sun and Detlef Lohse, is published in Physical Review Letters of February 24, 2017.

More recent news

Wed 18 Feb 2026Master's in Geo-information Science and Earth Observation recognised as an initial Master's

Wed 18 Feb 2026Master's in Geo-information Science and Earth Observation recognised as an initial Master's Wed 18 Feb 2026Prototype 'digital twin' helps Enschede better predict groundwater

Wed 18 Feb 2026Prototype 'digital twin' helps Enschede better predict groundwater Fri 13 Feb 2026UT nominations for Science Award

Fri 13 Feb 2026UT nominations for Science Award Thu 12 Feb 2026Drones accelerate and improve humanitarian aid delivery during disasters

Thu 12 Feb 2026Drones accelerate and improve humanitarian aid delivery during disasters Thu 12 Feb 2026UT Professor Frederic Schuller elected to the Academy for Excellence in Higher Education

Thu 12 Feb 2026UT Professor Frederic Schuller elected to the Academy for Excellence in Higher Education