Something remarkable is happening beneath our feet. A world where fungal threads weave their way between clumps of soil, while springtails feed on decaying plant roots. Where eggs wait for the perfect moment to hatch. Where a beetle sinks its jaws into a slug, which, after desperate attempts to break free, finally surrenders.

World Biodiversity Day 2024 marked the start of various activities on the University of Twente campus to share knowledge and enthusiasm about biodiversity. The 10th article in this series focuses on soil life, written by Jarno Winkel: a masters student in Biology at Wageningen University & Research. He has been fascinated by creatures crawling over the ground since childhood. During his studies, he specialized in soil life: knowledge he is eager to share with UT.

A world of wonder

Soil ecosystems are among the most diverse in the world, yet they often go unnoticed. The soil hosts countless organisms, from moles and earthworms to fungi and bacteria. Each organism plays a specific role: the behavior of one species influences the presence of another. Like a well-oiled machine, everything is interconnected. Because these processes take place out of sight, the soil ecosystem appears to be a true 'black box.'

There are different ways to categorize soil creatures. They can be classified by species groups, functional roles, body size, or the soil layer they inhabit. From a researcher's perspective, an organism's function is particularly interesting. What exactly does it do? And what can it tell us about the functioning of the soil system? Determining the precise role of each organism can be challenging. Their small size and underground lifestyle make observation difficult. However, scientists have been able to determine the roles of many creatures and their place in the soil food web.

Groups of species

Everyone is familiar with earthworms. After a heavy rain, you might see them lying on the ground. Earthworms need moisture to move above ground and find a mate. In the soil, they play a crucial role as detritivores (waste eaters). They consume dead organic material and, through their digestion, release nutrients for plants.

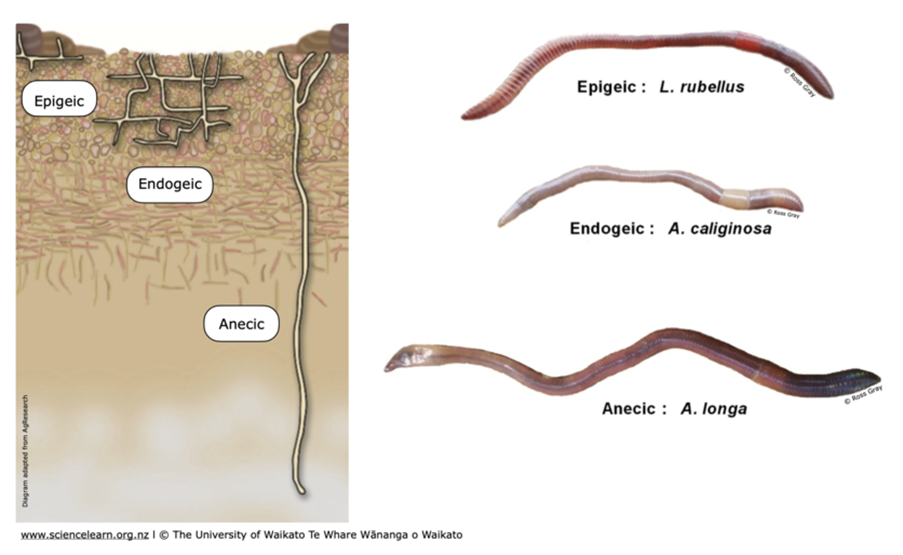

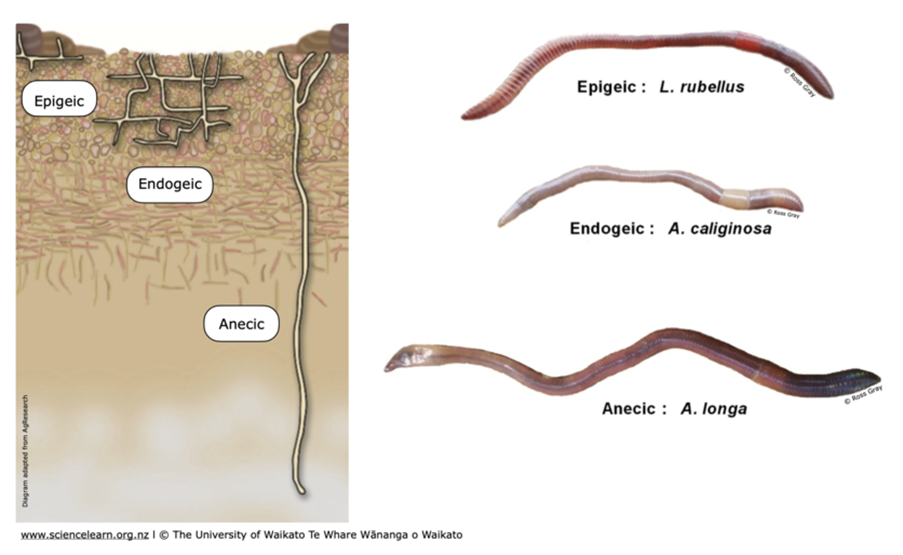

Different types of earthworms live in different soil layers and feed on various types of organic matter. Some emerge from their vertical burrows at night, searching for a suitable leaf, which they drag back underground—all without eyes! The Netherlands has 25 species of earthworms, which can be divided into three groups:

- Litter-dwelling worms (Epigeic): Live in horizontal burrows within the litter layer and are often dark-colored.

- Soil-dwelling worms (Endogeic): Found deeper in the soil, consuming organic material and bacteria along with soil particles. They remain underground their entire lives.

- Deep burrowers (Anecic): Live in vertical burrows that can extend meters deep. They feed above ground, dragging leaves into their burrows, mixing organic material from the surface with deeper soil layers. This speeds up decomposition and increases soil permeability, which is crucial for rainwater infiltration.

The ability to shape soil and their role in nutrient release make earthworms true ‘ecosystem engineers’. They manipulate their environment and create opportunities for other species.

Figure 1: Different types of earthworms. Source: www.sciencelearn.org.nz

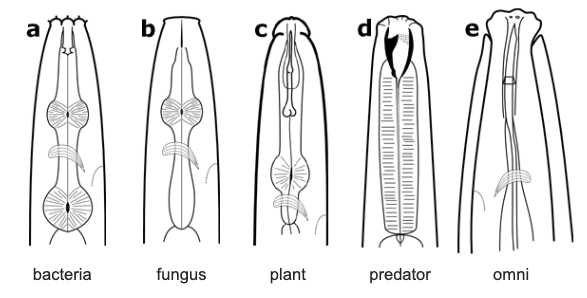

Another key player in the soil food web is nematodes. They are primarily known for their plant-parasitic lifestyle and the damage they can cause in agriculture. This perception is only partially justified: of the more than 1,200 nematode species in the Netherlands, only about 100 cause harm to plants.

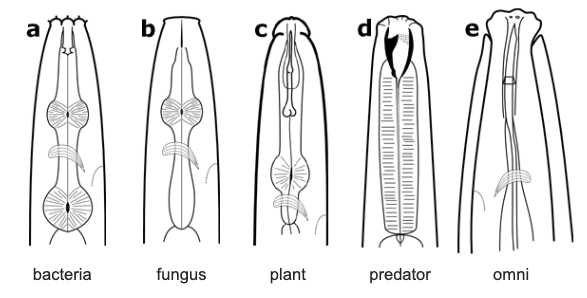

Nematodes are not only one of the most species-rich groups in the soil food web but also one of the most abundant. Researchers often classify nematodes based on their mouthparts, as these reveal their dietary preferences. Nematodes are an interesting group to study, due to their vast variation in size and lifestyle. The presence of different types of nematodes provides insight into how well-developed the soil food web is. If only detritivores and bacteria-feeders are found (at the bottom of the food chain), the food web is less developed than when predatory nematodes are also present.

Figure 2: Different mouth parts reflecting the feeding groups of nematodes.

Source: Ed Zaborski, University of Illinois.

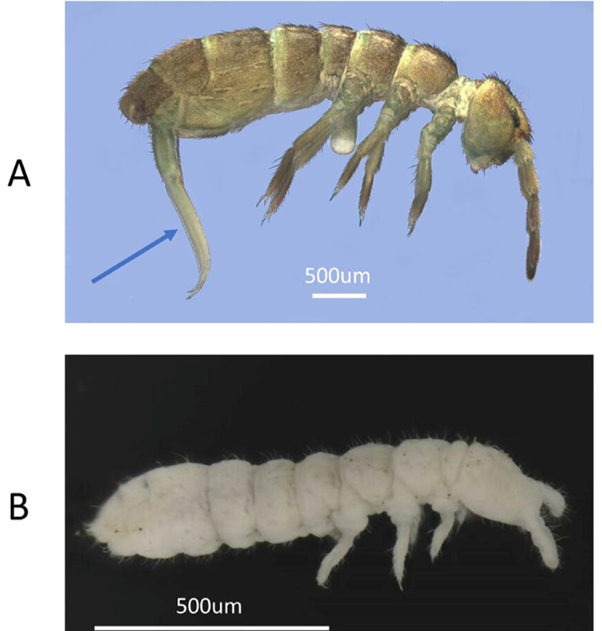

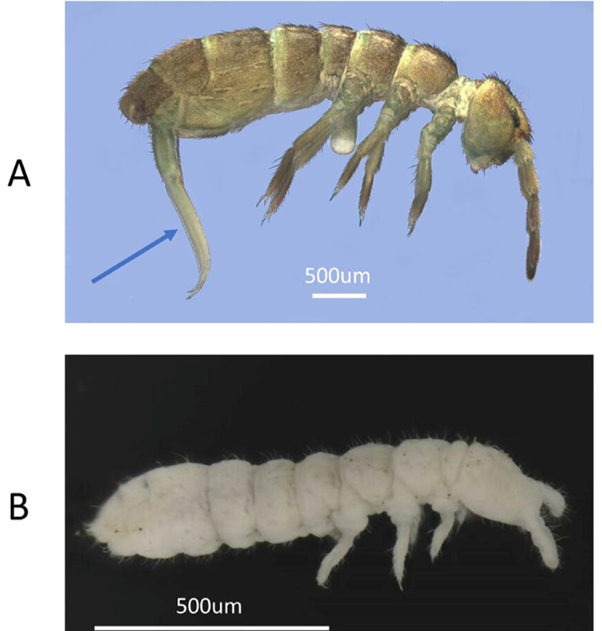

A lesser-known but remarkable group. These tiny creatures are six-legged arthropods, but not insects—they belong to their own group. They owe their name to the furcula: a fork-shaped appendage beneath their abdomen that acts as a spring to escape predators.

Figure 3: Springtail 'A' lives in the upper soil layer, springtail 'B' lives in deeper soil layers.

Source: University of Waikato.

In addition to this unique organ, springtails also possess a collophore: an organ that allows them to absorb moisture and regulate their metabolism. Springtails come in various shapes and sizes, from tiny spheres to elongated bodies, colorful or pale, hairy or smooth, with or without eyes. These physical traits indicate their lifestyle. Species lacking hair, pigment, a furcula, or eyes are adapted to life in deeper soil layers.

Figure 4: A springtail unfolding its collophore to protrude from its body. Source: Alexis Tinker-Tsavalas.

An essential group in the soil food web. In soil, mites can occur in high densities and fulfill various roles. Soil-dwelling mites mainly belong to the groups Oribatida, Prostigmata, Mesostigmata, and Astigmata.

- Oribatida are recognizable by their spherical shape.

- Prostigmata and Mesostigmata can be distinguished based on the position of their stigmata (respiratory openings). Prostigmata have these openings mainly at the front of their body, while Mesostigmata have them halfway along their body.

- Astigmata completely lack stigmata! Instead, they absorb oxygen directly through their skin.

Mites are an incredibly diverse group of arachnids, with over 2,400 species recorded in the Netherlands. Not all species live in soil—mites can be found in nearly every habitat, from Antarctica to the ocean, and from plants to animals (including humans). In soil, some mites feed on fungi or bacteria, while predatory mites (mainly Mesostigmata) consume other invertebrates, such as parasitic nematodes. As a result, they play a crucial role in regulating populations and maintaining a healthy soil food web.

Figure 5: Top left: Oribatida. Top right: Astigmata. Bottom left: Mesostigmata. Bottom right: a velvet mite (belongs to Prostigmata). Source: S.E. Thorpe; Daktaridudu; www.chaosofdelight.org; André Karwath.

Local soil life

Pinetum

The campus features several beautiful parks, including the unique Pinetum De Horstlanden. This arboretum, established in 1969, is a biodiversity hotspot due to its high diversity of conifers and pine trees. These trees also influence the soil life beneath them. Pine needle litter has a high carbon-to-nitrogen ratio, making it difficult to decompose. This primarily attracts species adapted to breaking down this tough material. Additionally, the acidic soil conditions lead to fewer earthworms in these areas.

Grassland and pine trees in Pinetum

Grasslands

Grasslands generally have a dense root system, resulting in a topsoil layer rich in organic matter. This makes them an ideal habitat for a wide range of soil organisms. A healthy grassland can support a soil community weighing up to 100 tons per hectare (equivalent to about 2,000 sheep per hectare!). Earthworms, particularly deep-burrowing species and litter-dwelling species, often dominate in grasslands. Mites and springtails are also found in high numbers, sometimes reaching up to 35,000 individuals per square meter.

Deciduous Trees on campus

Deciduous trees create a nutrient-rich and less acidic soil. This attracts a different composition of soil organisms. Their leaf litter is more easily decomposed, allowing less specialized detritivores to thrive. This environment also supports a higher diversity of nematodes, which are more sensitive to pH levels. Springtails and mites are often present in similar numbers as in the Pinetum.

Biodiversity at UT

Strengthening biodiversity on our campus is one of our sustainability goals at the University of Twente. By improving monitoring, we gain knowledge about biodiversity on campus in general, which helps us decide on the best ways to support it. In 2024, we started the yearly Bioblitz, in which anyone can help monitor species via the app ObsIdentify. Several activities were organised to raise awareness of biodiversity (such as bird observation). A biodiversity council was established, where CFM (Campus & Facility Management) consult with biodiversity enthusiasts on how maintenance can contribute to an improved habitat for species. Furthermore, thanks to a Climate Centre grant, we are working on making data on green maintenance and biodiversity accessible for research and education.

Would you like to find out more about sustainability at UT? Please go to utwente.nl/sustainability.