door Alexander van Deursen en Jan van Dijk

During the 1990s, researchers and policy makers began discussing the presence of a so-called “digital divide,” a distinction of people who do and do not have access to information and communication technologies (ICTs). The concept of the digital divide stems from a comparative perspective of social and information inequality and depends on the idea that there are benefits associated with ICT access and usage and negative consequences attending non-access and usage. Originally, the term “digital divide” mostly referred to gaps in access to computers. When the Internet became widely accessible in society and began to provide a primary means of computing, the term shifted to encompass gaps in Internet access. Defining the digital divide in terms of access to the Internet is now the most popular convention. However, other digital equipment such as mobile telephony and digital television are not ruled out by some users of the term digital divide.

The term digital divide probably has caused more confusion than clarification. According to Gunkel (2003) it is a deeply ambiguous term in the sharp dichotomy it refers to. Van Dijk (2005) has warned against a number of pitfalls of this metaphor. First, the metaphor suggests a simple divide between two clearly divided groups with a yawning gap between them. In fact the divide is more like a spectrum with on the one side people who use computers and the Internet for about every daily task and the people not using them at all at the other side. Secondly, it suggests that the gap is very difficult to bridge. A third misunderstanding might be the impression that the divide is about absolute inequalities, that is between those included and those excluded. In reality most inequalities of the access to digital technology observed are more of a relative kind (see below). A final wrong connotation might be the suggestion that the divide is a static condition while in fact the gaps observed are continually shifting.

An important theoretical distinction concerned is that between individualistic and relational conceptions of social inequality. The first conception departs from so-called methodological individualism (Wellman and Berkowitz, 1988). Differential access to information and computer technologies (ICTs) is related to individuals and their characteristics: level of income and education, employment, age, sex, and ethnicity, to mention the most important ones. This is the usual approach in survey research, which measures the properties of individual respondents. Making multivariate analyses of several individual properties and aggregating them to produce properties of collectivities, one hopes to find background explanations. An alternative notion of inequality uses a relational or network approach (Wellman and Berkowitz, 1988). Here the prime units of analysis are not individuals but the positions of individuals and the relationships between them. Inequality is not primarily a matter of individual attributes but of categorical differences between groups of people. This is the point of departure of the pioneering work Durable Inequality by the American sociologist Charles Tilly (1999). “The central argument runs like this: Large, significant inequalities in advantages among human beings correspond mainly to categorical differences such as black/white, male/female, citizen/foreigner, or Muslim/Jew rather than to individual differences in attributes, propensities, or performances” (Tilly, p. 7). In this conception gender inequality in using ICTs, for example, is not explained by the presumed characteristics of males and females (females having less technical interest etc.) but by the gender relations between them in which males first appropriate new technologies and exclude females in daily practice..

Despite these conceptual problems the term “digital divide” drew attention to the important issue of information inequality in scholarly and political communities at the turn of the century. Countries increasingly realized that the digital divide reduces the potential of the labor force and of innovation. Information and communication technologies were considered to be a growth sector in the economy that should be supported in global competition. Between 2000 and 2004, scientific and policy conferences concerning the digital divide were exceedingly popular, but attention to this matter began to decline in 2004 and 2005 (Van Dijk, 2006). On political and policy-making fronts, many observers, particularly those in rich, developed countries, reached the conclusion that the problem was almost solved, as a rapidly increasing majority of their inhabitants obtained access to computers, the Internet and other digital technologies.

The common current opinion among policy makers and the public at large is that the divide is closing between those who do and do not have access to computers, the Internet and other digital media. In some countries, Internet connection rates in households have reached the figure of 90 percent. Computers, mobile telephony, digital televisions and other digital media are becoming cheaper by the day, while their capacity to perform complex tasks increases. These media are introduced on a massive scale and into all aspects of everyday life. Several applications appear so easy to use that basic literacy supposedly is the sole prerequisite for using them. However, simultaneously defining the digital divide in terms of physical access to a technology is considered superficial by digital divide researchers; physical access alone is no longer considered to be the most important factor explaining information superiority observed. The emphasis is shifting to new dimensions, that is inequalities of skills and usage.

DIMENSIONS OF THE DIGITAL DIVIDE

First dimension: physical and material access

An important reason for the decreasing attention given to the digital divide in the first decade of the 21st century may lies in the fact that divides in physical access to the Internet are closing in most western countries. Concerns about acquiring physical access to digital media have completely dominated public opinion and policy perspectives in the last two decades. Indeed, these concerns are still paramount, as many people think the digital divide is closing because 90 percent of the population or more have access to a computer and the Internet. Such a number would put the Internet on a par with television as a media source. One should note that the diffusion of the Internet in the last two decades has occurred even faster than that of television. However, on a global scale the situation is different; in 2010 Internet access was estimated between 20 and 25 percent of the world population, while in many developing countries, Internet access is still restricted to less than ten percent of the population (UN/ITUstatistics).

Moreover, physical access is not equal to material access. Material access includes all costs related to the use of computers, connections, peripheral equipment, software and services. These costs are diverging in many ways, and people with physical access have very different computer, Internet and other digital media expenses. Considering the current economic crisis in the Western world, the problem of material access to computer and Internet resources for particular parts of the population might become more serious. In this regard, several scholars have pointed toward mobile phones and other portables such as tablet computers as technologies that have the potential to reduce the digital access divide. Mobile phones offer a more affordable means of access to the Internet than computers do when only simple applications that require small data capacity are used (Akiyoshi and Ono, 2008). They are supposed to offer a viable alternative for developing countries. However, one should also keep in mind that mobile phones are by no means a substitute for computers as they lack many advanced applications.

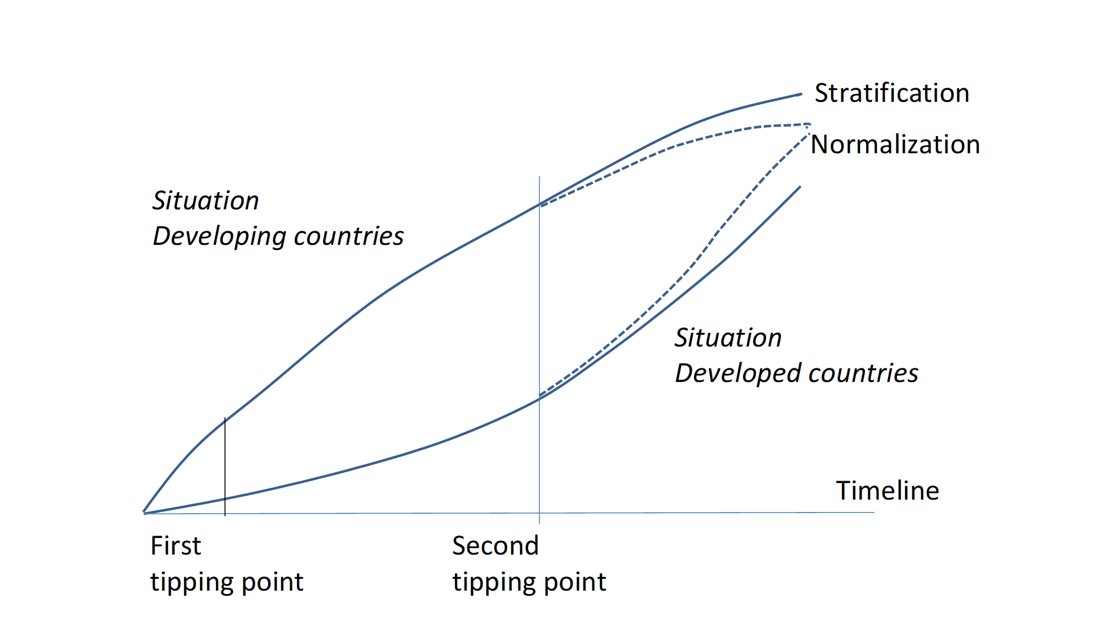

Whatever opportunities mobile phones offer, it is certainly a misconception to think that physical or material access to the Internet automatically bring all the benefits associated with Internet use. Indeed, it is rather schematic and superficial to conceive the digital divide in terms of a binary classification between those with and without physical access to computers or the Internet. Such a belief directly links rates of access to differences in material resources: one either does, or does not have the resources to establish a connection to the Internet. Moreover, such a belief assumes that having a connection correlates with having access to all the advantages the Internet offers. Compaine (2001), for instance, relied on the Diffusion of Innovations (DI) theory of Everett Rogers (1963/1995), who theorized that innovations would spread through society in an S-curve. The S-curve measures the relative speed with which members of a social system adopt a particular innovation and focuses on the time required for that innovation to be adopted by a certain percentage of the system (Rogers, 1995). The adoption rate accelerates at a first tipping point, called critical mass; at this point, an innovation has been so widely adopted that its continued adoption is self-sustaining (Markus, 1987). At a second tipping point diffusion begins to slow down as the market starts to reach saturation. Here the access divide starts to close. Van Dijk (2012) has portrayed the current situation of the physical access divide on a world scale in terms of the S-curve with the locations of developed and developing countries mapped into it.

Figure 1. Evolution of the Digital Divide of Physical Access in Time (Source: Van Dijk, 2012)

Figure 1. Evolution of the Digital Divide of Physical Access in Time (Source: Van Dijk, 2012)

(line below: access of categories of low education, low income and higher age; line above: access of categories of high education, high income and lower age)

The two curved lines in Figure 1 are splitting the main curved line that has the shape of a S to indicate that we have two sides or populations in the digital divide with different representations of the S-curve (that portrays the average). One curve is for those on the ‘wrong’ side of the digital divide, usually people with low education, low income and higher age and those on the ‘right’ side of the divide, mostly people with high education, high income and lower age. When the two lines come together the physical access divide is closing. However, at this point in time we still do not know whether it will close completely – this is called ‘normalization’ in the Figure - or that a gap will remain because the social categories in the higher curve continue to have a lead because they first adopt every new innovation in the field of digital media (for example the transition from narrowband to broadband). This is called ‘stratification’ by Norris (2001).

If Compaine and van Dijk were correct in applying DI theory to the digital divide, increases in physical access to the Internet would no doubt correspond to the S-curve measuring the adoption of innovations. From this point of view, the digital divide should steadily disappear as the diffusion rate reaches saturation, particularly when ‘normalization’ applies. The likelihood of the correspondence between the declining digital divide and the increasing rate of innovation diffusion would further be augmented as a result of the migration of the Internet to platforms such as digital television and mobile phones; indeed, the mistaken notion that the digital divide is a temporary problem of physical access has been reinforced by these migrations (Golding and Murdock, 2001). However, there are serious problems with applying the DI theory to the study of computer and Internet diffusion (Norris, 2001; Van Dijk and Hacker, 2003). Van Dijk (2005: 62-65) mentions several weak assumptions of this theory. First, why should the diffusion of each medium necessarily reach a hundred percent? Instead of this ‘normalization’ it might stop far before the stage of population-wide diffusion or become stratified (some categories keep adopting more and earlier than others). Second, while the DI theory assumes the existence of a single confined medium that does not change, in fact digital media devices often are combined (multimedia) and they continually change in functionality, quality, price and appearance (think about the history of the PC), Finally, the determinism of DI theory is striking: why should there be innovators, early adopters and early or late majority users with every medium?

Other dimensions come forwards: the second-level digital divide

Because it is wrong to assume that physical access to computers and the Internet automatically entails all benefits associated with their use, the digital divide should not be considered as a divide of physical access only. In the literature about the digital divide published after 2000, this conclusion comes forward stronger and stronger. Other dimensions have come forwards. Kling (2000), for instance, suggested a distinction between technical access (i.e., material availability) and social access (i.e., professional knowledge and technical skills necessary to benefit from information technologies). Attewell (2001) distinguished between a first digital divide and a second digital divide. Hargittai (2002), however, suggested what has become perhaps the most familiar distinction: that between first- and second-level digital divides. Besides these dimensions Warschauer (2003) also argued that factors such as content, language, literacy, educational level attained, and institutional structure must be considered. Van Dijk (2005) proposed a causal model with four types of access to ICTs: motivational access (e.g., the lack of the elementary digital experience by people who have no interest or feel hostile toward ICTs), physical access (e.g., the availability of ICTs), digital skills (e.g., the ability to use ICTs), and usage access (the opportunity and practice of using ICTs). He calls the shift from physical access to skills and usage a ‘deepening divide’ as unequal skills and usage are deeply entrenched in existing social inequalities and because they will deepen these inequalities again.

The dimension of motivation

Each of these scholars shares the following view: while gaps in physical access might be closing in certain respects, other digital divides have begun to grow. In his discussion of motivation access, for instance, van Dijk (2005) argues that the wish to have a computer and a connection to the Internet precedes physical access. Thus, many of those who remain on the excluded side of the digital divide do so for motivational reasons. According to van Dijk, there are not only ‘have-nots’ but also ‘want-nots.’ At the start of the diffusion of new technologies, motivational concerns are the strongest forces to stimulate or prevent the acceptance of those technologies. In several European and American surveys conducted between 1999 and 2003, half of those individuals unconnected to the Internet explicitly stated that they would refuse to seek a connection for the following reasons: no need or significant usage opportunities, no time or liking, rejection of the medium (e.g., Internet and computer games viewed as ‘dangerous’ media), lack of money, or lack of skills (e.g. ARD-ZDF, 1999b and a Pew Internet and American Life survey: Lenhart, Horrigan, Rainie et al., 2003). These observations lead us to one of the most confusing myths produced by popular ideas about the digital divide: that people are either in or out, included or excluded. To explain people’s motivations for using digital technologies, mental and psychological conditions are often mentioned in literature about the digital divide. Here, the phenomena of computer anxiety and techno-phobia are still relevant and continue to create barriers to computer and Internet access in many countries, especially among seniors, people with low educational background and segments of the female population (Brosnan, 1998, Chua, Chen and Wong, 1999, Rockwell and Singleton, 2002, UCLA, 2003)).

The skill dimension

In contemporary literature, inequality of Internet skills increasingly is acknowledged as a key dimension of the digital divide. Several terms are used to frame Internet skills, e.g. digital or information literacy, computer skills, ICT literacy or web fluency. To date, very little scientific research has focused on the actual level of digital skills possessed by various populations. Many large-scale surveys have revealed dramatic differences in skills among populations, including those populations in countries experiencing the extensive diffusion of new media (Van Dijk, 2005; Warschauer, 2003). Nevertheless, these surveys measure actual levels of digital skills only by asking respondents to estimate their own proficiency.

A better way to obtain valid and complete measurements of digital skills is to implement performance tests; such tests would require participants to perform those computer and Internet tasks that are regularly performed in daily life. Hargittai (2002) has begun to implement performance tests in this field. Asking 54 demographically diverse Americans to perform different Internet search tasks, she discovered enormous differences in levels of accomplishment and in the time needed to complete the tasks. In the Netherlands, Van Deursen and Van Dijk (2010, 2011) conducted performance tests in a university media lab on a cross-section of the Dutch population; more than 300 people were tested. Subjects who took the test showed a fairly high level of basic operational and formal skills, but they experienced much more difficulty in processing content-related information and in exercising strategic skills.

The results showed significant differences in performance between people of different ages and levels of education. Age primarily appears to be a significant contributor to the basic skills to use the Internet medium-related skills, as younger people perform better on these skills than older people do. In contrast, older individuals performed better where content-related skills, including information and strategic skills, were needed; this occurred in all instances where the older individuals possessed an adequate level of medium-related skills. However, because many seniors tend to lack medium-related Internet skills, they are seriously limited in their content-related skills. Nevertheless, this observation provides another perspective on popular notions about the abilities of the so-called ‘digital generation.’ It also shows that the skills inequality problem will not automatically disappear in the future and that life experience and substantial education of all kinds remain vital for acquiring digital skills.

The usage dimension

Aside from divergences in skill levels, the digital divide debate has increasingly drawn attention to the actual usage of the Internet. As a dependent factor, Internet use can be measured in several ways (e.g., usage time and frequency; number and diversity of usage applications; broadband or narrowband use; more or less active or creative use). Statistics regarding usage time and frequency are notoriously unreliable, as they rely on shifting and divergent operational definitions that are often determined by market research bureaus. These statistics give only some indication of the difference between actual use and physical access. It is certain, for example, that actual use diverges greatly from potential use. Furthermore, those who have a computer and/or Internet connection not always actually use them. Many assumed users actually use the computer or the Internet only once a week or a few times a month; some people never use them.

It is important to understand that when a physical access gap for a particular social category closes, usage of the medium concerned does not automatically equalize. Here the concept of ‘usage gap’ might apply. This concept is comparable to the concept ‘knowledge gap’ created in the 1970s by Tichenor, Donohue and Olien (1970). While the knowledge gap concerns the differential derivation of knowledge achieved through mass media and focuses, in particular, on mass media’s influence on perception and cognition, the usage gap concept is much broader and potentially more effective in terms of social inequality because this gap concerns differential uses of and activities with computers and the Internet in all spheres of daily life, not just the derivation of knowledge.

The usage gap closures becomes most apparent when looking at types of usage. It is generally assumed that some Internet activities are more beneficial or advantageous for Internet users than others. Some activities offer users more chances and resources to move forward in their career, work, education and societal position than others that are mainly consumptive or entertaining (e.g., Hargittai and Hinnant, 2008; Kim and Kim, 2001; Mossberger, Tolbert and Stansbury, 2003; Van Dijk, 2005; Wasserman and Richmond-Abbott, 2005). In terms of the theories of capital inspired by Bourdieu (1984), one could also say that certain Internet activities allow users to accrue more economic, social and cultural capital and resources than other activities. While some sections of the population will more frequently use those applications that have the greatest advantages for accruing capital and resources (work, career, study, societal participation, etc.), other sections will choose to use those entertainment applications that have little or no advantage for accruing capital and resources (e.g., van Dijk, 1999; Bonfadelli, 2002; Park, 2002; Zillien and Hargittai, 2009).

These differences in types of Internet use call into question the belief that growing up in a digital world results in an intuitive and unproblematic use of digital technologies (see Prensky, 2001). A difference exists between the personal and purposeful uses of technologies such as the Internet. Recently, several scholars have addressed the digital divide by attempting to classify Internet usage types. Some of these classifications take the uses-and-gratifications approach (Katz, Blumler and Gureitch, 1974) as a starting point, while others make use of the Technology Acceptance Model (Davis, 1989) or Social Cognitive Theory. Finally, there are scholars who account for differences in usage by grouping Internet users into use typologies (e.g., Ortega Egea, Menéndez and González, 2007).

THE DIGITAL DIVIDE AND INEQUALITY

What is the stake or concern of the digital divide? Do people with no access or limited access actually experience disadvantages? Two contra-arguments are given frequently by people relativizing the importance of the digital divide. The first argument is that people still have the traditional media at their disposal, which also deliver information and provide the needed communication channels. For those who have no Internet, a multitude of broadcasting and print media is available, and for those who have no access to e-commerce, physical shops abound. People searching new social contacts or romantic encounters do not necessarily require a social-networking site or an online-dating service, as the choice of physical meeting places is immense. Those individuals who want to make a reservation can still pick up the phone. The second argument is that the non-hierarchical nature of the Internet, in conjunction with the declining cost of computing technologies and their increasing user friendliness, encourages social leveling and undermines existing patterns of class, race, and gender inequalities (see Tambini, 2000).

However, after the times of the Internet hype around the turn of the century most scholars now agree that differences in Internet access among segments of the population tend to reinforce social inequalities. Witte and Mannon (2009), for example, argue that the Internet is both intertwined with and consequential for inequality. Considering the Internet in a paradoxical way, they contend that it is not only an exemplar of a free and open society but also an active reproducer and potential accelerator of social inequality. To understand this paradox one has to realize that the digital divide is more characterized by relative than by absolute inequalities (see Introduction). The digital divide signifies a spectrum of positions of inclusion and exclusion, not a binary classification of absolute inclusion and exclusion. Ninety percent or more of a population might have access to computers and the Internet while social and information inequality continue to rise on account of unequal material access, digital skills and usage opportunities.

A classification of resources suggested by Bourdieu (1984) is often mentioned in discussions of the Internet’s contribution to inequality. Bourdieu reimagined both Marx and Weber’s ideas of social inequality in industrial society by defining economic, cultural, and social capital. Economic capital reflects Marx’s ideas of property assets and other economic inequalities such as particular positions in the relations of production that might increase one’s capacities (Hoffman, 2008). Meanwhile, social capital consists of resources based on group membership, relationships, networks, and support; according to Bourdieu, social capital “constitutes the totality of current and potential resources connected to a durable network of more or less institutionalized relations characterized by mutual knowing or acknowledgements; in other words, social capital is a resource based on the affiliation to a group” (Bourdieu, 1984, p. 190). Finally, cultural capital is formed by knowledge, skills, education, and social-cultural distinction, all of which give a person a higher status in society.

All forms of capital defined by Bourdieu are applicable to the Internet. In fact, Internet use and Bourdieuian forms of capital reinforce each other. On the one hand, all forms of capital affect Internet access: economic capital is a requisite to acquire physical and material access to computers and the Internet; social capital is needed to learn from others how to connect to the Internet, how to use it and how to connect to those others; finally, cultural capital is required to cope with the diversity of content available to people of different cultural backgrounds. On the other hand, when these three requirements are met, the Internet in turn starts to affect the three forms of capital. For example, economic capital is increased by buying profitable resources online or by finding better jobs; social capital can be augmented by extending physical networks into virtual ones, perhaps increasing civic engagement and a sense of community (Katz and Rice, 2002); and cultural capital can be increased by using the Internet for learning purposes.

The result of the mutually determining relationship between forms of capital and the Internet is the usage gap discussed before which means that some individuals use the Internet in capital-enhancing ways, while others either do not use it or use it in less effective and less profitable ways; and the Internet may, of course, also be used simply for leisure (Hargittai and Shafer, 2006; Zillien and Hargittai, 2009). Furthermore, the intensive and extensive nature of Internet use among the well-off and well-educated correlates with an elite life-style, one from which those with less capital are excluded (Van Dijk, 2005; Witte and Mannon, 2009). The result of this last observation is that groups with fewer forms of capital are likely to be affected in negative ways by the Internet: flights will be booked, concerts will be sold out, jobs will be given away, and dates will primarily be granted to those having access. This is the main counter-argument against the argument that traditional channels still offer all opportunities called above. Rather than encouraging equality, the Internet tends to reinforce social inequality and can lead to the formation of more permanent disadvantaged and excluded groups unless deliberate economic, cultural and educational policies are installed by responsible policy makers (Golding, 1996; Van Dijk, 2005). As Witte and Mannon (2009) contend, Internet access can be understood as a tool for the maintenance of class privilege and power as the inequalities upon which they rest are reproduced from one generation to the next.

Much theoretical work on the concept of network society also suggests that the Internet increases social inequalities. Castells (1999) considers the divide between those who are and are not networked as one of the major axes of social inequality (Castells, 1999). He contends that the particular framing of ICTs in the context of global, informational, and increasingly de-regulated capitalism has been a major factor in the increase of inequality, in general, and of social exclusion, in particular. Because technological access is essential for both the improvement of living conditions and personal development, ICTs deepen discrimination and inequality in the absence of deliberate, corrective policies (Castells, 1999).

Van Dijk (1999, 2006, 2012) defines the network society as a form of society that organizes its relationships into media networks; these networks gradually replace or merge with the social networks of face-to-face communication. For Van Dijk, media networks have become the nervous system of society and are shaping the primary means of social organization and the most important structures of modern society. In a network society, information should be considered a positional good, with some positions creating better opportunities than others for gathering, processing, and using valuable information (Van Dijk, 2005). The positions people have in networks determine their individual potential power; this concept reflects the Weberian idea that human relationships should be considered alongside economic assets when discussing social inequality. When someone in a network society has only a marginal position or no position at all, he or she experiences social exclusion because the opportunities are reduced.. Meanwhile, those who have a central position in society achieve social inclusion and thereby increase their power, capital, and resources (Van Dijk, 2005). With unequal positions comes an unequal distribution of positional goods. According to the mechanism of opportunity hoarding, those individuals who have central positions in networks tend to appropriate more goods, to exert more control over particular facilities and to wield greater power within networks; they then capture the returns of these resources and use them to reproduce the boundary between themselves and those who are socially excluded (Tilly, 1999).

In conclusion, most recent scientific literature on the digital divide suggests that the Internet has the potential to strengthen traditional kinds of inequality rather than to ameliorate them. Unequal access to the Internet has varying consequences in several areas of society: the economic (e.g., acquisition and maintenance of jobs), the social (e.g., development and maintenance of social contacts), the political (e.g., voting and other kinds of political participation), the cultural (e.g., participation in cyber-culture), the spatial (e.g., the ability to lead a mobile life) and the institutional (e.g., recognition and attainment of citizens’ rights).

REFERENCES

- Akiyoshi, M., and H. Ono. 2008. The diffusion of mobile Internet in Japan. The Information Society 24:292–306.

- Attewell, P. (2001). The First and Second Digital Divides. Sociology of Education, 74(3), 252-259.

- Bonfadelli, H. (2002). The Internet and knowledge gaps: a theoretical and empirical investigation. European Journal of Communication, 17(1), 65-84.

- Bourdieu, P. (1984). Distinction: a social critique of the judgment of taste. London: Routledge.

- Castells, M. (1999). Flows, networks and identity: A critical theory of the international society. In M. Castells, et al. (Eds.), Critical Education in the New Information Age. Rowman and Littlefield: Lanham.

- Castells, M. (2004). The network society: a cross-cultural perspective. Northampton, MA: Edward Elgar.

- DiMaggio, P., & Hargittai, E. (2001). From the ‘Digital divide’ to ‘Digital inequality’:Studying internet use as penetration increases. Working Paper Series 15: Princeton University Center for Arts and Cultural Policy Studies.

- DiMaggio, P., Hargittai, E., Celeste, C., & Shafer, S. (2004). From Unequal Access to Differentiated Use: A Literature Review and Agenda for Research on Digital Inequality. In Neckerman, K. (Ed.), Social Inequality (pp. 355-400). New York, NY: Russell Sage Foundation.

- Golding, P. (1996). World-wide Wedge: Division and contradiction in the global information infrastructure. Monthly Review, 48(3), 70-86.

- Golding, P., & Murdock, G. (2001). Digital divides: communications policy and its contradictions. New Economy, 8(2), 110-115.

- Compaine, B.M. (2001). The Digital Divide: Facing a Crisis or Creating a Myth? London: MIT Press.

- Davis, F.D. (1989) ‘Perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use, and user acceptance of information technology’, MIS Quartely 13(3): 319-340.

- Hargittai, E., & Shafer, S. (2006). Differences in actual and perceived online skills: the role of gender. Social Science Quarterly, 87(2), 432-448.

- Hargittai, E. (2002). Second-Level Digital Divide: Differences in people's online skills. First Monday, 7(4).

- Hargittai, E., and Hinnant, A. (2008) ‘Digital Inequality: Differences in Young Adults' Use of the Internet’, Communication Research 35(5): 602-621.

- Hoffman, R. (2008). Socioeconomic differences in old age mortality. Dordrecht: Springer.

- Katz, E., Blumler, J.,and Gurevitch, M. (1974) ‘Utilization of mass communication by the individual’, in J. Blumler and E. Katz (eds) The uses of mass communication: Current perspectives on gratifications research, pp. 19–34. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage.

- Katz, J.E., & Rice, R. (2002). Social Consequences of Internet Use: Access, Involvement, and Interaction. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Kling, R. (2000). Learning about information technologies and social change: The contribution of social informatics. The Information Society, 16(3), 217- 232.

- Kim, M, and Kim. J. (2001) ‘Digital Divide: Conceptual Discussions and Prospect’, in W. Kim, T.W. Ling, Y.J. Lee, and S.S. Park (eds) The Human Society and the Internet, pp. 136-146. Berlin. New York: Springer

- Lenhart, A., Horrigan, J., Rainie, L., Allen, K., Boyce, A., Madden, M., et al., 2003. The ever-shifting Internet population: A new look at Internet access and the digital divide. Washington, DC: Pew Internet and American Life Project. Retrieved August 28, 2004, from http//:www.pewinternet.org .

- Markus, L.M. (1987). Toward a “Critical Mass” theory of interactive media. Communication Research, 14(5), 491-511.

- Mason, S.M., & Hacker, K.L. (2003). Applying communication theory to digital divide research. IT&Society, 1(5), 40-55.

- Mossberger, K., Tolbert, C.J., and Stansbury, M. (2003) Virtual Inequality: Beyond the Digital Divide. Washington, DC: Georgetown University Press.

- Norris, P. (2001). Digital Divide: Civic engagement, information poverty and the Internet worldwide. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Ortega Egea, J.M., Menéndez, M.R., and González, M.V.R. (2007) ‘Diffusion and usage patterns of Internet services in the European Union, informations research’, International Electronic Journal 12: 302.

- Park, H.W. (2002). The digital divide in South Korea: Closing and widening divides in the 1990s. Electronic Journal of Communication, 12(1-2).

- Prensky, M. (2001). Digital natives, digital immigrants. On the Horizon, 9(5), 1-6.

- Rogers, E.M. (1995). Diffusion of Innovations. New York, NY: Free Press.

- Steyaert, J. (2002). Inequality and the digital divide: myths and realities. In S. Hick & J. McNutt (Eds.), Advocacy, activism and the internet (pp. 199-211). Chicago: Lyceum Press.

- Selwyn, N (2006). Digital division or digital decision? A study of non-users and low-users of computers. Poetics, 34(4-5), 273-292.

- Tambini, D. (2000). Universal Internet access: A realistic view. Retrieved from http://www.csls.ox.ac.uk/

- Tichenor, P.J., Donohue, G.A., & Olien, C.N. (1970). Mass media flow and differential growth in knowledge. Public Opinion Quarterly, 34(2), 159-170.

- Tilly, C. (1999). Durable Inequality. University of California Press.

- Van Deursen, A.J.A.M. & Van Dijk, J.A.G.M. (2011). Internet Skills and the Digital Divide. New Media & Society, 13(6), 893-911.

- Van Dijk, J., & Hacker, K. (2003). The Digital Divide as a complex and dynamic phenomenon. The Information Society, 19(4), 315-327.

- Van Dijk, J., & Hacker, K. (2003). The Digital Divide as a complex and dynamic phenomenon. The Information Society, 19(4), 315-327.

- Van Dijk, J. (2006). Digital divide research, achievements and shortcomings. Poetics, 34(4-5), 221-35.

- Warschauer, M. (2003). Technology and Social inclusion: Rethinking the Digital Divide.Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

- Wasserman, I.M., and Richmond-Abbott, M. (2005) ‘Gender and the Internet: Causes of Variation in Access, Level, and Scope of Use’, Social Science Quarterly 86: 252–70.

- Willis, S., & Tranter, B. (2006). Beyond the digital divide. Internet diffusion and inequality in Australia. Journal of Sociology, 42(1), 43-59.

- Witte, J.C., & Mannon, S.E. (2009). The Internet and social inequalities. New York: Routledge.

- Zillien, N., & Hargittai, E. (2009). Digital Distinction: Status-Specific Types of Internet Usage. Social Science Quarterly, 90(2), 274-291.