Experiences with comparative judgement

“THIS ONE'S GOOD, BUT THE OTHER ONE’S BETTER!”

By Marieke van Geel and Priyanka Pereira – ELAN, department of teacher development

If you need to make a decision, it is likely that you will do this based on some kind of comparison, either consciously or subconsciously. If you are presented with several options, comparing is intuitive. It is therefore easier to decide which of two options is better, compared to the other, than deciding on the individual quality of each option one-at-a-time. In education, comparing two students’ work against each other, and doing that for a lot of combinations of pairs, is known as comparative judgement.

In the Educational Science and Technology-master course Assessing & Monitoring Performance in Education, students learn about the design and use of assessment in various ways. Aside from the more traditional approaches to judgment, for example, by applying absolute-analytical rubrics, we introduced our students to the concept of comparative judgement. We wanted our students to gain more hands-on experiences with technological innovations, and, therefore, used the Comproved tool to experiment with comparative-holistic judgement. In this blogpost, we will discuss the concept of comparative judgment, the tool we used, and our students’ experiences.

Interested in using Comproved in your teaching? Make sure to read our ‘tips and tricks’ and reach out to the TELT-team.

Comparative judgement

How does it work?

An assessor is presented with two students’ work and asked to pick the better product based on some agreed global descriptor (for example: which one is more creative?). The assessor must pick one of the products – there cannot be a tie. Then, the assessor is presented with other pairs of students’ work, one pair at a time. For every pair, the assessor must pick the better product. This whole procedure is conducted with multiple assessors. The different assessors may get the same pairs of products, or they may get different pairs. If two assessors get the same pair, it can happen that they each pick a different product as the better one.

The data that is generated is fitted to a statistical model that produces a standardised score as a parameter estimate (along with the standard error) for each product. Using the parameter estimates and the standard errors, the products can be ordered from worst to best to give a scaled rank order or a scaled distribution of the products. If needed, experts can then estimate the score of the average product, and then the model can be used to estimate the scores of every other product, depending on the odds that they are better than the average product.

What is it used for?

Comparative judgement is used to maximise reliability and validity when evaluating higher-order learning. On the one hand, while objective tests are reliable, they are not valid for evaluating higher-order learning. On the other hand, while performance-based tests are valid, their judgement is also subjective and, therefore, they are not reliable. Comparative judgement allows for the evaluation of valid performance-based learning products by multiple assessors, thus maximising validity and reliability.

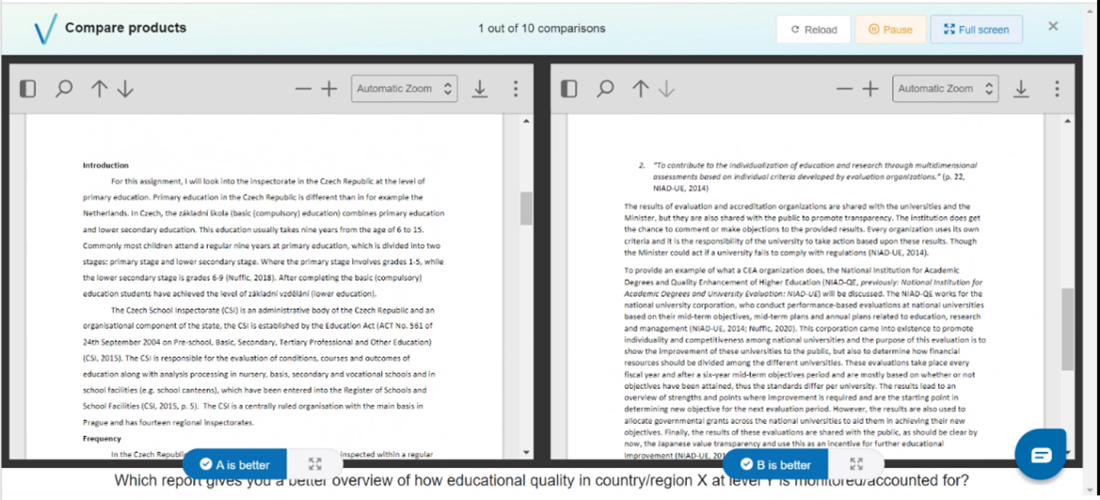

The tool: Comproved

The Comproved tool is an app that allows assessors to apply comparative judgement in an easy way. Two students’ work are presented next to each other, and the assessor is asked to identify the best product. In addition, the assessor can be asked to provide feedback on each product. Comproved can be used by external assessors, but it can also be used by students for peer judgement or peer feedback.

On the teacher dashboard, you can see the rank order of the products, the standardized score for each product, and the reliability of the comparisons. You can also focus on assessors and comparisons. For example, you can see the number of comparisons each (student) assessor made and the median amount of time they spent on each comparison. Also, when specific assessors seem inconsistent in their judgements, this is flagged.

Students’ experiences

In the Assessing & Monitoring Performance in Education course, students experimented with applying comparative-holistic judgement and analytical-absolute judgement, by reviewing their peers’ assignments in both ways. The student assignment that was reviewed was a report about a school inspectorate system in a country of choice.

Although we do not have sufficient data to draw conclusions regarding the reliability of the judgements and scores, we would like to present our students’ experiences and insights. Aside from the fact that several students indicated that the written reports were too long to be able to stay focused, an additional issue was that some students were tempted to judge the inspectorate system that was described, instead of the report their peer had written.

Several students mentioned that comparative judgement was especially easier and quicker when the two works were distinct. When the quality of the two works was more similar, it was considered difficult to identify 'the better one.’ Especially when students regarded both works as ‘good’ they felt it was ‘unfair’ to identify ‘the better one’ - as if they would devalue the quality of the ‘also good but not better of the two’ work. In general, assigning points based on an analytical rubric was deemed easier: “you had points to check for".

With regard to the Comproved program, students all indicated it was easy to use: “It's a well-designed program and the interface looks simple”. They recommended asking assessors for feedback, to support students in improving their work, although this would demand even more time and effort from assessors.

An important point to note is that, even though we do not have sufficient data due to time constraints, in both approaches, the same assignments were identified as being at the top and bottom when the items were ordered according to the judgements.

Tips & Tricks for the Use of Comparative Judgement

Why should you use it?

- Since we usually base our decisions on comparisons, either consciously or subconsciously, comparative judgement is more intuitive than absolute judgement, and hence it is easier to carry out.

- Because comparative judgement is easier to carry out, humans are better (i.e., more consistent) at comparative judgement than we are at absolute judgement. Therefore, comparative judgement is more reliable. Multiple assessors lessen the impact of each individual assessor.

- Comparative judgement does not require each assessor to make a very precise judgement of each product because they do not need to give an exact mark. They just need to judge whether the product is better or worse than another product. And even if they get the judgement “wrong,” it does not matter too much because the product will be involved in other comparisons by the same and other assessors, so it will work out in the end.

- Comparative judgement does not require explicit, detailed assessment criteria to achieve high reliability. It just requires a global descriptor. This means that assessors do not need to spend time and effort to familiarise themselves with the criteria. They can directly start judging.

- The added advantage of not needing assessment criteria is that comparative judgement takes care of the shortfalls of rubrics. First, it is ideal for subtle or complex constructs that are hard to operationalize in terms of explicit criteria. Rather than these constructs being defined by the criteria, they are defined by the collective knowledge and opinion of the assessors. Second, it is ideal for open-ended tests where students can give a range of responses that are difficult to anticipate and cover in rubrics. No matter what students include in their products, the assessors’ knowledge and opinion is sufficient to judge the product.

- Comparative judgement does not necessarily require expert assessors. It has been found that even peer students can produce reliable and valid results without training. Although, it must be said that experts may reach a high level of reliability after fewer comparisons. But it does not matter much because we usually have a much larger number of students available, so they can produce a high number of comparisons even without too many comparisons being produced by each student.

- Comparative judgement can be used in a wide range of contexts for a wide range of learning products.

- Comparative judgement can be used as a learning tool. When students look at their peers’ work, they become aware of different ways of looking at the same assignment and can learn from each other.

What should you keep in mind when using it?

- The only factor that affects the reliability of comparative judgement is the number of comparisons per product. If you want to produce a reliable scale to assess n products, you need to have a total of 10n to 37n judgements. This would require a sufficiently large number of products and/or a sufficiently large number of assessors to have a high enough number of comparisons per product. If you have very few products, you can compensate by using more assessors. Or if you have very few assessors, you can ask each assessor to make more comparisons.

- While comparative judgement can be used for a wide range of learning products, consideration does need to be given to the amount of time assessors are provided with to make their comparisons. The greater the size of each product, the more time they need for each comparison. Also, the more comparisons they need to make, the more time they need in total.

- Comparative judgement may sometimes be frustrating for assessors. It may be difficult to pick which product is better when there is only a small difference in quality. It may also be difficult to pick which product is better when each of the two products have some pros and some cons.

- Comparative judgement is not well suited for formative assessment since it does not provide the students with specific feedback. More modern applications do allow students to provide feedback in the form of either an explanation of their choice or the pros and cons of each option. However, it is found that this slows down the process.

- It is not easy to translate the scaled rank order into grades. It requires a multi-step standard-setting exercise.

If you would like to use Comproved in your education, please feel free to contact the TELT team!

Want to read more about comparative judgement?

Jones, I., & Wheadon, C. (2015). Peer assessment using comparative and absolute judgement. Studies in Educational Evaluation, 47, 93-101. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.stueduc.2015.09.004

Lesterhuis, M., Bouwer, R., van Daal, T., Donche, V., & De Maeyer, S. (2022). Validity of comparative judgment scores: How assessors evaluate aspects of text quality when comparing argumentative texts. Frontiers in Education, 7. https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2022.823895

Verhavert, S., Bouwer, R., Donche, V., & De Maeyer, S. (2019). A meta-analysis on the reliability of comparative judgement. Assessment in Education: Principles, Policy & Practice, 26, 541–562. https://doi.org/10.1080/0969594X.2019.1602027