“After finishing my Bachelor’s in Advanced Technology at the University of Twente, I wanted a master’s that mixed everything I love — materials science, chemical engineering, physics, and electrical engineering. I like to see a problem from different angles and figure out how it all fits together. That’s why I chose the Master’s in Nanotechnology at the University of Twente: it integrates all these fields to teach me how to design nano-devices. Basically, nano-devices are super tiny, often only a few nanometres in size (a nanometre is one-billionth of a metre), and can be used in different fields, such as medicine and electronics.

I decided to combine it with the Master's in Chemical Science & Engineering as both overlap in areas like materials science. Nanotechnology leans more into the physics side, while Chemical Science & Engineering dives deep into how molecules behave and interact. This combination is valuable because it lets me categorise and understand how materials behave under different conditions.

Tiny scale, big decisions

Another reason why I chose this Master's is because I’m learning about the machines and tools that make nanotechnology possible, such as advanced microscopes and fabrication equipment. For instance, I’m learning about different types of microscopes that allow us to see and analyse the tiny things we create. We use optical microscopes, and I’ve learned how lenses work together to zoom in incredibly far while still keeping the image sharp. But what amazes me are the electron microscopes, which use a beam of electrons instead of light to reveal even smaller details. Understanding how these microscopes work is crucial because it lets me see the nanoscale structures I'm designing and ensures they're accurate.

I’m also learning when not to use nanotechnology, and I find this really important. A lot of people think nanotechnology is this magic solution for everything, but that isn't always the case. For example, there’s been a lot of hype around carbon nanotubes: they're often seen as the answer to making materials stronger or conducting electricity better. But sometimes, nanotechnology can make things more expensive or just not work well with the other materials. So, a big part of what I’m learning is recognising when nanotechnology isn’t the best option, which I think is really cool because it teaches me to think critically.

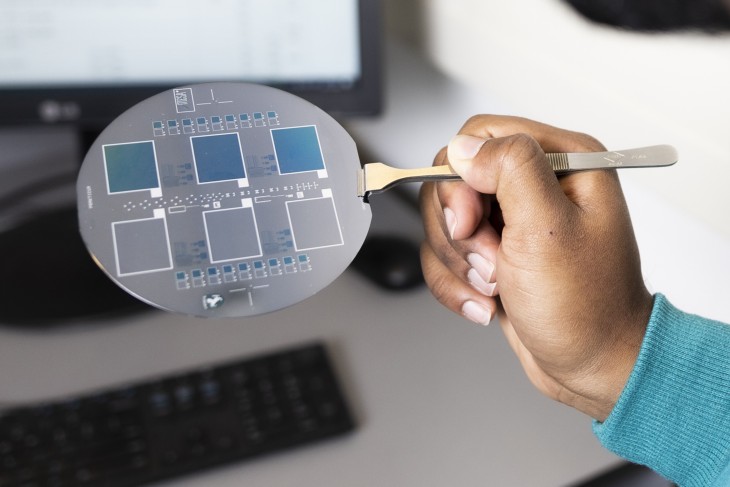

Moreover, the NanoLab at the University of Twente is pretty awesome: you get to use all these high-tech tools in the cleanroom to run experiments. In my opinion, it’s one of the things that makes the programme stand out.

Hands-on learning

One of the most memorable projects I’ve worked on was designing an e-reader for blind people that displays Braille, where each letter is a raised dot they can touch. At first, it might not sound like nanotechnology, but here’s how it fits in: when you flip a page on the e-reader, it needs to quickly refresh the dots to show new text. The dots were a few millimetres, and we had a tiny piston inside the device that moved them up or down, thus making them either detectable or invisible to the touch.

What I loved about the project was that everyone in the team had a different bachelor's background, which made for great collaboration. For example, there was someone from mechanical engineering who could simulate the forces on the device; a physics student who was great at modelling how everything would behave, and an electrical engineering student who figured out how to power the device. Even though we only designed the e-reader and didn’t build it, working on this project taught me a lot about how different fields in nanotechnology come together to create something useful for a real-world application.

Aspirations

As for my plans, I'm interested in research and development, however, I might consider doing a PhD first. I’m not sure about all the possibilities yet, so I’m excited to explore where this path will take me.”