The social significance of the European Union: between naïve optimism and doom-mongering

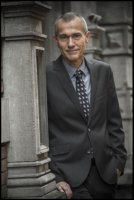

Frank Vandenbroucke studied economics in Leuven and Cambridge, UK, and received his D.Phil. in Oxford. He was Minister for Social Security, Health Insurance, Pensions and Employment in the Belgian Federal Government (1999-2004), and Minister for Education and Employment in the Flemish Regional Government (2004-2009).

He was professor at the University of Leuven (KU Leuven) from 2011 until October 2015. He is now University Professor at the University of Amsterdam (UvA). He also teaches at the University of Antwerp (UA), where he holds the chair “Herman Deleeck”.

His current research focuses on the impact of the EU on the development of social and employment policy in the EU Member States.

He is the chair of the Academic Council on Pension Policy, set up by the Belgian Government.

For publications, see www.frankvandenbroucke.uva.nl/publicaties or Research Gate (www.researchgate.net).

The social significance of the European Union: between naïve optimism and doom-mongering

The social impact of European integration has been a matter of debate and controversy, already since the creation of the European Common Market in 1958. Are deep European integration and the development of robust national welfare states at odds with each other? Frank Vandenbroucke ponders this question and sketches a social agenda for the EU.

The founding fathers of the European project optimistically assumed that economic integration would contribute to the development of prosperous national welfare states. Market integration and freedom of movement would lead to growing cohesion both between and within countries. Social policy could safely remain at the national level. In contrast, pessimists argued that there was a fundamental conflict between the logic of the European project (a priority for ‘opening’) on one hand and the logic of national welfare states (protection premised on the possibility of ‘closure’) on the other hand. European integration, as it was conceived, would inevitably erode the social acquis of the most advanced member states.

Historical experience supports neither the optimist nor the pessimist view. European integration and flourishing welfare states can go hand in hand. However, that is not what we observe today. If we wish to reconnect with the inspiration of the European founding fathers, we have to reconsider the relationship between the EU and national welfare states. This implies defining a social ambition and delineating a role for the EU. Frank Vandenbroucke explains what this means for the social agenda of the EU.