ASSIGNMENT

The armed forces protect what we hold dear: a world in which people can find security, stability, prosperity and freedom. This is why Defence personnel work daily to ensure peace and security, often in difficult and sometimes dangerous, life-threatening circumstances. This commitment underscores the nearly unique nature of the armed forces: the readiness and willingness to engage in combat when necessary. To enable this, Defence, as the ‘sword’ of political leadership, exercises the monopoly on the legitimate use of force. This authority carries significant responsibilities for Defence personnel. Consequently, Defence traditionally places great emphasis on values and norms, morality, ethics and mutual solidarity, which are elements that converge in effective leadership.

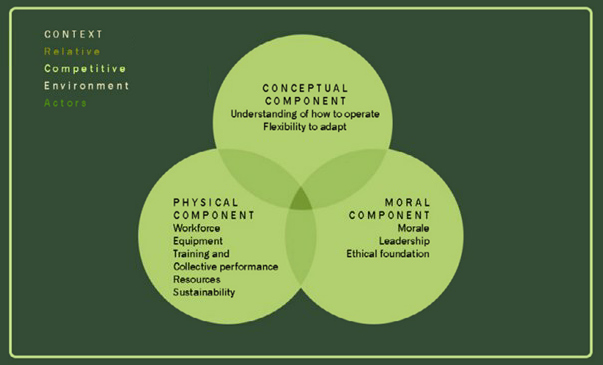

Fighting power describes the operational effectiveness of the Army. It recognises that military forces do not simply consist of people and equipment, but have interconnected an interdepending physical, moral, and conceptual properties as depicted in Figure 1 Fighting power is inherently contextual and it is determined by how well a force (our own, allied, or enemy) can adapt to the character of the operation(s) in which it is engaged.

Figure 1

The Model of Fighting Power (British Ministry of Defence, 2021. army-leadership-doctrine-web.pdf)

The physical component provides the means to fight and consists of personnel, equipment, sustainability and resources. The conceptual component is the force’s knowledge and indeed the application of doctrine, kept relevant by its ability to learn and adapt. The moral component concerns the human aspect of fighting power and is arguably the most important, as success on operations is dependent upon people to a greater degree than equipment or doctrine.

Specific information

The Dutch Airmobile Brigade (AASLT) is a rapidly deployable light infantry unit of the Royal Netherlands Army, specialised in air assault operations by foot and helicopter. This brigade is a rapidly deployable light infantry combat unit composed of over 2,000 men and women. Air Mobile troops move on foot, with light vehicles, or via helicopter or transport aircraft. The red beret worn by Air Mobile troops is the international symbol of paratroopers and airborne forces. Training and exercises within the brigade are characterised by a high tempo of action and continuous physical and mental challenges. Soldiers are therefore accustomed to activity rather than inactivity.

However, in an actual Article-5 operation (NATO, 2023), conditions can change dramatically. Soldiers may be required to endure long periods of waiting, often in forward positions, without access to digital entertainment or personal devices. Added to this is the uncertainty of waiting for the opponent’s first move; soldiers may not know when or even if action will take place.

This combination of low stimulation and prolonged uncertainty may generate boredom and cognitive underload, which in turn can impact the moral component of soldiers: their motivation, cohesion, trust in leadership, and willingness to act under pressure. Understanding how boredom, cognitive underload, and uncertainty affect the moral component is essential to ensure resilience and operational effectiveness.

The moral component

The moral component is not easily defined; however, Messink (2025) found that it represents the human foundation of fighting power, encompassing motivation, resilience, leadership, and cohesion. It is shaped at multiple levels (Messink, 2025):

- Individual: motivation, psychological resilience, trust in leadership.

- Unit: cohesion, camaraderie, discipline.

- Organisational: leadership, training, sense-making, working conditions.

- External: societal support, public opinion, family, geopolitics.

The moral component is always present but often implicitly influenced. Therefore, it is important to do research on the effect boredom or cognitive underload has on the moral component, as this can have an impact on combat situations.

Boredom & cognitive underload

Research suggests that boredom can affect a person’s behaviour as well as someone’s emotions (Yucel & Westgate, 2021). When being bored during a pre-combat situation, this might be harmful for that specific moment, as well as the combat situation after. Furthermore, a high level of automation in UAS, coupled with uneventful missions or legs, puts the operator at risk of most of the above-mentioned problems: low workload, leading to boredom, lack of SA and eventually loss of skills. This in turn can lead to complacency and trust issues (Nationaal Lucht- en Ruimtevaartlaboratorium, 2011). Boredom can negatively impact soldiers’ cognitive performance, particularly when prolonged inactivity is combined with uncertainty, making it harder to stay focused and make sound decisions (TNO, 2022). Moreover, Ziller (2024) highlights how prolonged periods of boredom during night operations, marked by waiting and monotony, can undermine soldiers’ vigilance and motivation, yet are abruptly interrupted by sudden moments of terror that demand immediate readiness. As it can have a tremendous impact on soldiers, the team and the mission, it is of paramount importance to systematically review the impact of boredom on the moral component, as this can affect their fighting power.

Assignment

Conduct a literature study that defines boredom and cognitive underload and its effect on the moral component, especially under conditions of waiting and uncertainty (preferably in a military context).

- Researching whether the literature identifies a link between boredom/cognitive underload and the moral component (motivation, cohesion, will to fight). Identifies preventive measures that can be applied before deployment to prepare young soldiers for uncertain environments lacking any digital device and feeling bored.

KEYWORDS

Boredom; uncertainty; low-stimulation environments; moral component; resilience; motivation; cohesion; military psychology; Article-5 readiness.

BACKGROUND INFORMATION ORGANIZATION

The section Psychology of Conflict, Risk and Safety at the University of Twente has a distinctive and unique profile in the areas of risk perception and risk communication, conflict and crisis management and the antecedents of risky, antisocial and criminal behaviour. It currently includes 16 research staff members and 8 PhD students. We work from both a psychology and an engineering perspective and cooperate with other scientific disciplines, based on the “high tech, human touch” profile of the University of Twente.

AVAILABILITY

Usually anytime. This internship is open to 1-2 students. Please note that this project can also be part of your master's thesis.

INTERESTED?

Please contact the internship coordinator Miriam Oostinga (m.s.d.oostinga@utwente.nl).

LITERATURE

- Messink, B. (2025). Scoping review naar moral component van fighting power.

- Yucel, M., & Westgate, E. (2021). From electric shocks to the electoral college: How boredom steers moral behavior.

- TNO (2022). Effects of concurrent and subsequent physical activity on cognitive performance: Theories and a pilot study conducted and discussed within a trilateral project arrangement between Canada, Netherlands and Sweden.

- Ziller (2024). Boredom and Terror: Fighting at Night.

- https://www.nato.int/cps/en/natohq/official_texts_17120.htm

- https://www.sto.nato.int/document/a-psychological-guide-for-leaders-across-the-deployment-cycle-2/