Wilfred has made it his academic mission to design chips inspired by the human brain and to make 'inanimate' material intelligent. 'Making self-learning materials is one of the major scientific challenges of the 21st century,' he says.

According

to Wilfred, this new, intelligent material must have memory, deal independently with its environment and regulate its own actions. 'Until now, intelligence has been the domain of living systems. But would it be possible to bring intelligence to the realm of inanimate matter? Ultimately, we want to make more efficient computers, or super-smart brain implants.'

No digital chips

Wilfred is researching systems that are themselves adaptive and thus come close to the efficiency of the human brain. In doing so, his team is joining forces with neuroscientists. 'We need to dare to move much more away from digital chips that are in our phones or laptops. They are very strong, but they consume energy. Especially in applications with a lot of data. If we want to make that chip learning and adaptive, we don't have to make a software change, but we have to evolve the chip itself.'

Energy consumption of our brain

Only 20 watts. That's the amount of energy our brain uses on average. 'While your brain has an awful lot of computing power and, above all, adaptive capacity,' says Wilfred. 'Your brain is actually a kind of hardware that isn't finished the moment it rolls out of the factory. Of course, there are some things pre-programmed from evolution, but there is a lot that still needs to be formed. That offers opportunities. A brain-inspired computer chip needs to be designed much more for a specific application. A chip that shouldn't be able to do everything, from word processing to data to you name it, for example.'

cochlea

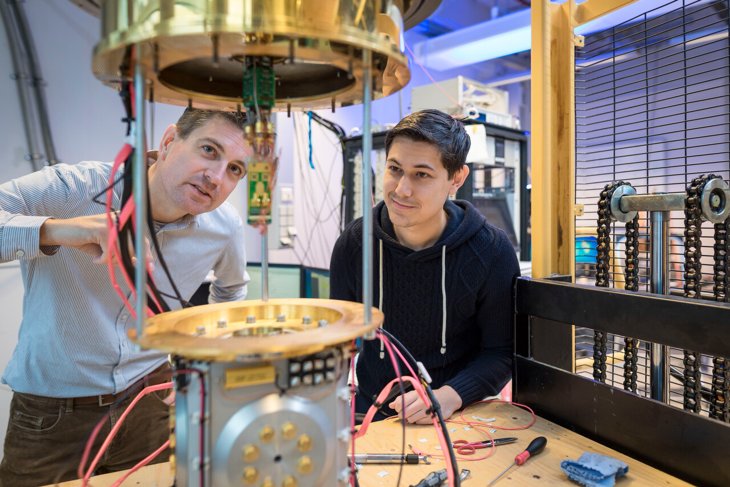

One of the concrete applications Wilfred is working on is being developed in collaboration with car manufacturer Toyota and IT company IBM. In other words, global players. Within the HYBRAIN project, the partners are working on a chip that is very good at speech recognition, but in a completely non-digital way. 'You feed those chips with speech through a microphone. The chip then uses intrinsic material properties, which are very similar to the cochlea in your ear. A human cochlea filters a lot before a signal even goes to your brain. So it's very intelligent material, but also very complicated.'The chips Wilfred is working on convert vibrations into an analogue signal. 'Normally, you then make such a signal digitally, because then you can do something with it with your chips. But that takes energy. With speech recognition, you're also talking about separate frequency domains, a different spectrum, and so on. You guessed it: that's a lot of energy.'

The chips should eventually be used in the latest (electric) cars, for example for voice control or a sensor that monitors the noise of the engine. Wilfred: 'There are so many digital sensors in a car these days, it scares you. Get some out of it and then you might be able to drive about fifty kilometres further on your battery.'

Wilfred teaches in the UT Nanotechnology (Master's) and Bachelor's programmes in Electrical Engineering.